party finance in Bangladesh, while being a central question in policy formulation, has always remained in the dark. Political parties raise and spend large sums with little transparency, weak enforcement of disclosure rules, and minimal accountability. That culture has seeped into student politics, where future leaders learn the craft. Student organisations oscillate between unregulated financing and abrupt shutdowns when they become inconvenient. When elections do occur, the rules are so inconsistent that they breed cynicism rather than trust.

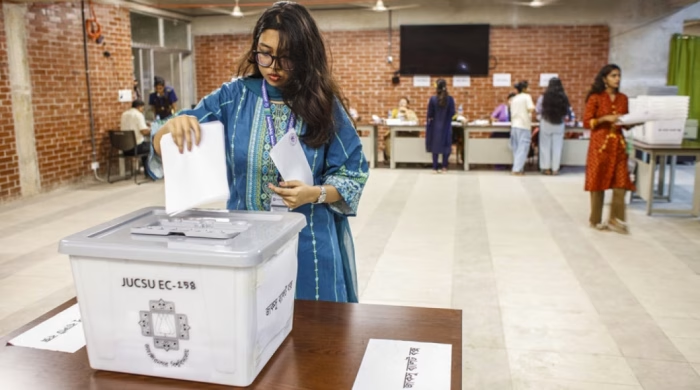

Looking into the rulebooks of student union elections, which have taken place or are about to, there are laws but very little implementation of them. At Dhaka University, DUCSU electoral authorities ban all financial transactions, including crowdfunding, yet provide no legitimate framework for financing a campaign. The result is predictable: funding goes underground and opaque sources gain leverage.

Jahangirnagar University takes the opposite route with explicit spending caps—Tk 4,000 for hall candidates and Tk 7,000 for central candidates—but sidesteps the core question of where the money may come from.

Rajshahi University’s RUCSU and Chittagong University’s CUCSU echo DUCSU’s blanket prohibitions without designing workable alternatives. As demand for elected student unions grows across campuses, the absence of a clear, uniform policy produces a system that bans without guidance, caps without disclosure, and leaves enforcement to chance.

The consequences are structural, not cosmetic. After the July uprsing, student politics should have been rebuilt on ideas and mobilisation. Instead, under vague financing rules, campaigns reward those who can buy visibility and convenience.

Social mobilisation theory is blunt on this point: participation is not only shaped by individuals’ political ideology but also by the networks or groups they are embedded in. Building and activating large networks requires organisation, logistics, and steady money. Relentless online promotion has become a new tool of campaigning, and Facebook ads and digital boosting are central to it, yet entirely unregulated. This creates an imbalance between candidates with strong political backgrounds and individual candidates with no backing.

The impact of unregulated campaign financing is twofold. First, students at their formative stage of political grooming are exposed to a culture of unchecked rules and practices. Second, and perhaps most critically, unregulated money opens the door to external interference. This pattern is reinforced by research on party finance regulation by D. L. Wiltse, R. J. La Raja, and D. E. Apollonio.