He wrote not to lull but to awaken, not to flatter society but to strip it of its ornamental hypocrisy

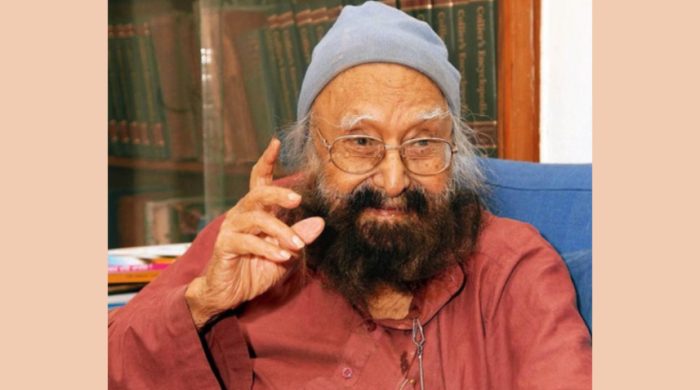

There are writers who comfort their readers, and there are writers who unsettle them into thinking. Khushwant Singh belonged emphatically to the second breed.

In a career spanning more than seven decades, he emerged as an institution of dissent, wit and moral candour. He wrote not to lull but to awaken, not to flatter society but to strip it of its ornamental hypocrisy.

In a literary culture often inclined towards reverence, Singh preferred irreverence; where others cloaked ideas in solemnity, he sh0arpened them with humour. Few writers managed, as he did, to be at once beloved, feared, quoted and quietly transformative.

A journalist, novelist, editor, historian, columnist, translator, provocateur, moralist in disguise, he inhabited India’s public life for over six decades, watching the nation grow from colonial shadow into democratic turbulence.

His life’s defining trauma, like that of many Indians of his generation, was partition. It became a wound that bled into his imagination and ethics.

And through all of it, his pen remained loyal to one principle – honesty without apology.

A life shaped by history

Born in Hadali of undivided Punjab in 1915, Khushwant Singh came of age alongside the Indian subcontinent’s political awakening.

He studied law in Lahore and London, initially entering diplomacy, serving in India’s foreign service in Canada and Britain. Yet bureaucracy never quite suited a man so restless. He left diplomacy for journalism.

Khushwant Singh believed newspapers should not merely report but provoke. He made space for literary journalism, political scepticism and social introspection.

Partition as moral memory

No work captures Khushwant Singh’s emotional gravity better than “Train to Pakistan”.

Published in 1956, the novel is deceptively simple. A border village, Mano Majra, where Sikhs and Muslims coexist until the hatred arrives. Khushwant Singh does not sermonise. He observes. Violence creeps in not as spectacle but as inevitability, shaped by fear, rumour and political betrayal.

Unlike epic nationalist narratives, his partition writing focuses on ordinary bodies caught between abstractions. Lovers are separated, friendships corrode, moral certainties fracture. What makes the novel enduring is not its historical value but its ethical tenderness.

He understood that history is most cruel not in parliaments, but in railway wagons and abandoned homes.

Partition remained his recurring metaphor for fractured humanity.

Even in later essays and columns, he returned to it as a reminder that civilisation, when intoxicated with ideology, forgets compassion first.

Wit as an unapologetic weapon

If tragedy gave Khushwant Singh depth, humour gave him edge.

His wit was not decorative; it was surgical. He distrusted sanctimony, especially when wrapped in politics, religion or social prestige.

Singh’s columns often punctured pomposity with elegant mischief. He once remarked that he wrote “to irritate people into thinking”. That irritation was deliberate.

In books such as “The Company of Women” and “Delhi”, he explored desire, power and hypocrisy with frankness that scandalised polite society.

Sex in his writing is neither voyeuristic nor moralistic. It is human, flawed, comic and revealing. He used intimacy to expose the psychology of ambition, loneliness and self-deception in urban India.

“Delhi”, in particular, stands as a remarkable literary experiment. Through the voice of a hijra narrator, Singh traces centuries of the city’s history, fusing erotic memory with imperial ruins. It is both chronicle and confession, history seen through the pulse of flesh and power.

Singh never pretended virtue. Instead, he dissected it.

Beyond fiction, Singh made history readable. His two-volume “History of the Sikhs” remains a foundational text, combining scholarship with narrative grace. Where academic histories can feel embalmed, Singh’s moved with rhythm. He saw history not as chronology but as lived emotion.

Similarly, his translations and retellings of Sikh scriptures and traditions were not acts of blind devotion, but of cultural stewardship.

He respected religion without surrendering his rational scepticism. He admired faith but distrusted fanaticism.

That balance, reverence without obedience, made Singh unusually modern in temperament.

Popular columnist as public philosopher

For decades, Khushwant Singh’s columns became ritual reading across Indian subcontient.

Whether discussing politics, corruption, sexuality, social decay or spiritual emptiness, he wrote with conversational elegance.

He refused to hide behind euphemism.

When politicians lied, he called it lying. When society performed virtue, he asked whom it truly served.

Yet he was never cruel for sport.

Beneath the satire lay human sympathy. Even when criticising, he searched for psychological causes, not merely political ones. His writing carried an old-fashioned moral intelligence, one that believed literature must speak to conscience as much as to style.

In many ways, Khushwant Singh functioned as literary conscience, irreverent but ethical.

Khushwant Singh influenced generations of Indian journalists and writers by demonstrating that elegance need not surrender to timidity.

He proved that a foreign language, when handled with cultural intimacy, could carry local experiences without sounding colonial or ornamental.

Khushwant Singh’s style, crisp yet lyrical, urbane yet rooted, shaped the grammar of the Indian subcontinent’s English prose in newspapers and literature alike.

More importantly, he normalised intellectual fearlessness.

Writers learned that disagreement is not disrespect, and satire is not betrayal.

Accolades and contradictions

Khushwant Singh received numerous honours, including the Padma Bhushan and later the Padma Vibhushan. Yet, in characteristic fashion, he once returned the Padma Bhushan in protest against Operation Blue Star, revealing a rare ethical consistency — honour meant little if conscience objected.

This gesture captured Khushwant Singh perfectly. He accepted recognition, but never allowed it to own him.

He lived long, wrote longer, and aged with undiminished curiosity.

Even in his nineties, his columns sparkled with youthful scepticism. Death, to him, was merely another subject for humour.

Stories about Singh circulate like folklore. He kept his afternoons reserved for writing and his evenings for conversation. His Delhi home became a salon where politicians, artists and journalists mingled under his amused gaze. He valued punctuality, good whisky and better arguments.

Once asked what kept him productive, he replied with characteristic economy — discipline, curiosity and a refusal to pretend virtue.

He believed writers must observe life honestly, not theatrically.

Perhaps his greatest anecdote is his life itself: A man who moved through empire, partition, nationhood and globalisation without surrendering intellectual independence.

In an age increasingly allergic to nuance, Khushwant Singh’s literary works remain instructive — reminding that literature is not a decoration of society but its interrogation; that humour can coexist with grief.